'I have to be taller' : the unregulated world of India's limb-lengthening industry.

Young Indians are paying for complex,painful procedures despite the absence of medical oversight in the race to improve marriage and career prospects.

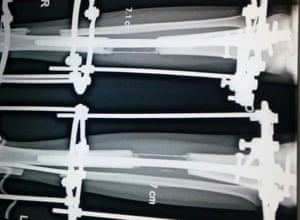

Komal never told her friends where she went for six months last year. The 24-year-old, fromt he town of Kota, in western India, went to see Dr Amar Sarin, an orthopaedic surgeon in Dehli, who made her eight centimetres (3in), a procedure which involved breaking the bones in her legs and wearing a brace until she could walk again.

Her parents had to sell the family’s ancestral lands so she could get the surgery, but for Komal, the extra height is worth it. “I have so much confidence now,” she says. “I was just 4’ 6” [137cm]. People used to make fun of me and I couldn’t get a job. Now my younger sister is doing it, too.”

Her parents had to sell the family’s ancestral lands so she could get the surgery, but for Komal, the extra height is worth it. “I have so much confidence now,” she says. “I was just 4’ 6” [137cm]. People used to make fun of me and I couldn’t get a job. Now my younger sister is doing it, too.”

In a country where height is considered attractive, Komal is one of a growing number of young Indians using their increasing prosperity to improve their marriage and career prospects, and fuelling a cosmetic surgery boom.

However, limb lengthening surgery is completely unregulated in India and many of the surgeons performing it lack experience. As it also carries a certain stigma, the Guardian has chosen not to reveal Komal’s real name.

Dr Sarin says: “This is one of the most difficult cosmetic surgeries to perform, and people are doing it after just one or two months’ fellowship, following a doctor who is probably experimenting himself. There are no colleges, no proper training, nothing.”

Prospective patients appear undaunted, including those from abroad. India’s reputation for cheap and well-trained doctors attracts people from around the world, in a medical tourism industry worth an estimated $3bn. Cosmetic surgeries make up a large slice of that figure, drawing increasing numbers from countries in Europe, America and elsewhere where procedures can cost four or five times as much.

Dr Sarin, who started offering the surgery five years ago, has treated 300 patients already, and only a third of them are from India. “It is a growing trend in India,” he says. “I get around 20 calls a day, with people telling me ‘I want to be tall, I have to be taller.’”

One man who had surgery in 2015 says he met at least 20 doctors before deciding to go ahead with the procedure. “Many of the doctors I approached had only done it once or twice before, and one had never ever done it before. I searched for around one year before I found the right person to do it.”

Last month, an ethics committee in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh summoned orthopaedic surgeons who had operated on a 23-year-old man, after doctors raised concerns about why “unusual, experimental surgery” was performed. The surgery divides orthopaedic specialists in India, many of whom contend that the surgery is extremely difficult to perform and can cripple people for life.

Dr Sudhir Kapoor, the president of the Indian Orthopaedic Association, says: “We don’t recommend for people to do this surgery except for in very rare cases. These surgeries are not done routinely and there’s a high risk of complications.”

Limb lengthening surgery was pioneered in the 1950s, in a small Soviet town called Kurgan in Siberia. Its inventor, a Polish man named Gavriil Ilizarov, once dismissed as a quack, became known as the “magician from Kurgan”, after he performed orthopaedic operations on people including an Olympic high jump champion. Ilizarov never intended for his technique to be used for cosmetic purposes; his work was targeted at people who had had accidents or were born with limbs of different lengths.

Now, the controversial Ilizarov technique is being used by surgeons across India, though with many modern modifications to make it quicker and less painful. Sarin, who has earned an international reputation for his skill in performing the surgery, says he struggled with the ethics of performing it at first. “I used to wonder whether what I’m doing is right, but when I saw how much their self-esteem was improving, I decided to keep going,” he says.

The surgery should be used only as a last resort, he adds. “We often turn people away,” he says, explaining many of his patients have suffered acute psychological disorders. “We try counselling first, but we’ve had patients who even threaten to commit suicide if I refuse to do the surgery. Twice I’ve had to call the police in emergency situations like that.”

Though he has performed the surgery successfully on hundreds of people, Sarin admits: “It’s madness to do it.”

Still, he feels successful limb lengthening can transform a person’s life: “You can barely recognise them. It’s worth it when you see how much their self esteem grows.”

Citation:

Doshi, Vidhi. "'I Have to Be Taller!'" The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 08 May 2016. Web. 10 May 2016. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/09/i-have-to-be-taller-the-unregulated-world-of-indias-limb-lengthening-industry>.

The very concept of "limb-lengthening" sounds absolutely mortifying but the reality of having your legs broken and wearing a cast until you can walk again all to be three inches taller is exactly that: mortifying. As the bulk of our societies push people to fix, improve and change themselves to fit-in better, plastic surgeries are only going to become more popular. Obviously in India, marriage prospects and employment are high stakes and are definitely enough to push people to have this risky limb-lengthening surgery. There are high enough stakes for a family to sell ancestral lands to afford such surgeries that could leave the patient completely crippled for the rest of their life. But the author of this article, Vidhi Doshi, shows the ethical dilemma surgeons who originally set out to improve the lives of those who had had accidents or were suffering are now facing. Now they are meeting the demands of self-improvement because of dissatisfaction. Although Doshi lists the great lengths that people all around the world will go to have such a surgery, he is biased against the surgery because he writes more about the ethical dilemma or the risks of the surgery over statistics of more patients getting jobs post-surgery. He also shows that although there are those that are desperate, many come from all around the world to India for the purpose cheap self-improvement surgeries. Medical tourism is a billion dollar industry in Indian because many patients come from all around the world to have affordable and fast surgeries in India. So, there are a lot of people that such an article can be aimed at, even if just for them to question whether the battle with ethics is worth another celebrity's nose. If a person wants to change one thing about themselves, they will find another part to be dissatisfied later. It is a vicious cycle of never quite being good enough until after another surgery and then another. But so much of this is linked to a self-improvement cultures that are only growing. So, after reading the final line of this article of a doctor proclaiming that the improvement in self-esteem is worth it, do you think it is worth it?

Measure

Measure